By Jenny L. Feick, PhD

If you have ever attended one of the GDTA’s trail work trips you have likely helped to clear shrubby vegetation from the Great Divide Trail and its immediate vicinity. Shrubs are the woody perennial plants that are smaller than a tree with multiple permanent stems branching from or near the ground.

At times, on a hot day amid the flies, you may have heard some volunteers cursing the so-called alders. You may have also heard a few choice words from thru-hikers battling their way through a dense thicket of what they are calling willows in as yet unmaintained sections of the GDT. But have you ever wondered if those shrubs they were blaspheming were really what they thought they were? While on the GDT, have you ever thought about what the presence or absence of certain shrubs can tell us about the environment through which the trail passes? Or have you considered what clues they provide that could aid the GDTA in route-finding and trail maintenance? If so, read on. The shrubs you see are not all alders or willows! Learning about them can reveal useful information affecting one’s safety on and enjoyment of the GDT, as well as the route’s viability and longevity.

Like all plants species, different types of shrubs have evolved to exploit different environmental conditions. Some like it wet; others prefer dry areas. One finds certain shrub species only in open areas; others thrive in shady areas. Some shrubs can tolerate windswept rocky alpine ridges. Others are only found in the deeper soils of valley bottoms. There are shrubs that help other plants to grow by improving the fertility of the soil. Other species exude toxins into the soil to repel their floral competitors. Certain shrubs produce delicious edible berries that attract bears and other wildlife; others generate leaves with medicinal qualities, and yet others wield spines that can cause serious allergic reactions in some people. It’s good to know what you’re dealing with and not to make assumptions when it comes to the more than 35 species of shrubs that can be found along the GDT (see Table 1).

However, identifying shrubs can be challenging. It’s helpful to get a good field guide like Alpine Plants of the Rocky Mountains by Kershaw, Mackinnon and Pojar (2017). There’s also the old classic, Trees, Shrubs and Flowers to Know in Washington and British Columbia (1996)by C.P. Lyons and Bill Merilees. However, you might not want to carry these while on the GDT. In areas where you can access the internet you can look up information on E-Flora BC[1] or Project Plant Identification Alberta[2]. You may also want to consider joining iNaturalist, one of the greatest citizen science initiatives ever launched[3]. While you learn about what you are seeing, you contribute useful information on what species can be seen along the GDT to a data base that scientists use to identify species, including rare and undocumented ones, and to develop species range maps.

Considering Shrubs in Route-Planning

In general, when route-planning, it’s best to find areas where the soil is relatively dry, coarse, and fairly well drained, like south or west facing side slopes, ridgetops, or alluvial fans. Shrubs that tend to grow on those slopes can include bearberry (kinnikinnick), shrubby cinquefoil, prickly rose, Western snowberry, chokecherry, Canada buffaloberry (soopolallie or soapberry), saskatoon (serviceberry), wax currant, black gooseberry, thimbleberry, all three species of the coniferous juniper (Rocky Mountain, common and creeping), Rocky Mountain maple[4], and rock willow. You want to avoid the wet soil areas in valleys characterized by most willow species, water birch, and red osier dogwood as well as cool, moist north or east facing mountain slopes thickly carpeted with green or Sitka alder, white-flowered rhododendron, false azalea, huckleberry and blueberry bushes.

While the presence of certain berry bushes may indicate a preferred soil type for trail construction and maintenance, trail planners need to determine if bears habitually frequent the area during the hiking season because of their need to access this important food source (e.g. huckleberry, Canada buffaloberry), and if so, consider routing the GDT away from that area.

Considering Shrubs in Trail Maintenance

The shrub species that prove most challenging for GDTA volunteers to clear, primarily because of their dense prolific growth (especially after pruning), include the following:

- many of the willow species found in wet areas, including smooth willow, which can carpet floodplains and other recently disturbed sites and Barratt’s willow, which forms dense fragrant thickets of balsamic resin-coated hairy-leafed bushes, and hybrids[5];

- the two species of alder found in the Rockies, the green or Sitka alder[6], which forms dense thickets, especially in recently lightly burned areas with moist soils and some tree cover, and speckled alder (gray alder), which colonizes open boggy areas;

- the red osier dogwood grows rapidly in a loose branching formation, with upright stems, horizontal branches, and densely growing underground stems in organically-rich soils along streams and other wet areas.

- the white-flowering rhododendron, a deciduous, acutely branching shrub in the Ericacea (Crowberry/Heath/Heather Family) with erect-ascending stems to 150 cm tall, that grows densely along the margins of cool, moist coniferous woods and frequently along shady stream sides, bearing dainty clusters of mildly citrus-scented white flowers and attractive bright green leaves; and

- the false azalea, another heath, with its loosely grouped, spreading branches, sticky stems, and small rusty bell-like flowers thrives in moist, shady areas like the steep slopes of mountains. The leaves and/or flowers emit an unpleasant skunky odour if crushed.

In addition, spiny shrub species (the junipers, especially common juniper, prickly rose, raspberry, wax currant, black gooseberry, creeping Oregon-grape) can pose problems if a significant amount of clearing proves necessary. Volunteers need thick canvas or leather gloves and protective clothing. While very rare along the GDT and only occasionally encountered in low, moist valleys on the B.C. side of the divide, one needs to be wary of the devil’s club. WorkSafe BC issued a toxic plant warning that details a severe eye injury one forestry worker received from this shrub. The spikes on this shrub’s stems and leaves prompt serious allergic reactions in some individuals. Besides the protective clothing and gloves, WorkSafe BC advises donning safety goggles and carrying tweezers and anti-inflammatory cream in case thorns get imbedded in one’s skin. One has to be careful not to mow down innocent plants with a similar-shaped leaf (minus the prickly bits) like the cow-parsnip, a valuable food plant for wildlife.

In the high elevations through which the GDT passes, many shrub species grow slowly (the junipers, shrubby cinquefoil, Rocky Mountain willow) and others never get tall (mountain heather[7], bearberry, grouseberry, crowberry, creeping Oregon-grape, bog birch, dwarf birch, rock willow), and thus do not require a lot of pruning.

Considering Shrubs as You Hike the GDT – There’s More than Meets the Eye

Wildlife need their Veggies, Too

Ironically, some of the shrubs GDTA volunteers grumble most about are essential food sources for the hoofed mammals (ungulates) and other wildlife that we enjoy watching from the trail. Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), elk (Cervus canadensis) and moose (Alces alces) like to browse on willows and red osier dogwood. Smooth willow provides wintering ungulates with a rich source of calcium and phosphorous. This species of willow constitutes a large part of the diet for snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) in the Rocky Mountains, and is vital for beavers (Castor canadensis). White-tailed ptarmigan (Lagopus leucura) eat the buds and catkins of dwarf birch and songbirds eat insects attracted to the catkins.

Alder is extremely valuable for wildlife in the vicinity of the GDT. Elk munch on the tender young shoots, while white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and mule deer feed on the leaves and twigs. Muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus), snowshoe hares, and red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) also eat alder twigs and leaves, while beavers eat the bark. The seeds, buds, and catkins provide an important source of food in winter for numerous song birds, including redpolls, pine siskins (Spinus pinus), crossbills, finches, grosbeaks and sparrows, as well as some game birds. Mountain alder is an important component of white-tailed ptarmigan winter forage. In some areas, moose and caribou (Rangifer tarandus) browse alder in the winter. The caterpillars of several species of butterflies feed on Sitka alder. Its catkins offer a source of pollen for honeybees, native bees, and other insects during the spring.

Canada buffaloberry foliage provides a moderate quality browse for mule deer, white-tailed deer, bison (Bison bison), elk, and snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) especially when the plants are dormant in winter and fall. Elk, deer, moose, caribou, beaver, and snowshoe hare feed on the foliage of highbush cranberry and Sitka mountain ash, both evident in moist valleys on the west slope of the Great Divide such as the Blaeberry in Section D of the GDT.

Primarily grazers of grass, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) eat the fresh leaves and buds of willows, saskatoon, and Rocky Mountain maple. Mule deer and elk also dine on the leaves and twigs of saskatoon. Other shrubs preferred by mule deer include Western snowberry, thimbleberry, and chokecherry. They even eat prickly rose and Oregon grape. Amazingly, elk nibble on common juniper despite its coarse spiky needles.

Sometimes, a species’ route to its salad bowl is not that obvious. Wildlife biologists recognized that although mountain alder was a principal component in mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus) foraging areas, goats did not appear to browse on it. They eventually learned that alder shrubs provide ground cover that lessens snow accumulation, making desirable species like lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina) more accessible to mountain goats.

Just Desserts

Floral nectar and even the sap from shrubs provide vital quick energy fuel for a variety of species. Bees frequent wild roses and wolf willows. Butterflies, including the tiny spring azure (Celastrina ladon), consume the nectar in the inner flowers of the high bush cranberry, as do ants. The hoary comma butterfly (Polygonia gracilis) prefers the flowers of wild gooseberry and currant bushes. Mourning cloak butterflies seek their sustenance from willow catkins. Western snowberry flower nectar attracts bees, flies, ants, butterflies, moths, and hummingbirds.

Porcupines (Erethizon dorsatum), red squirrels, snowshoe hares, mice, and voles nibble at thin-barked shrubs to access the sweet sap. Hummingbirds and red-naped sapsuckers (Sphyrapicus nuchalis) have been observed feeding on water birch sap and the insects attracted to the sap.

Berry Nice

The many shrubs with edible fruits (berries, rose hips, etc.) provide a staple food source for bears and other wildlife as well as occasional sustenance for hungry hikers[8]. The berries of Canada buffaloberry are well-known as a highly favored food of grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) and black bears (Ursus americanus), but also sustain ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus). Highbush cranberries get eaten by bears, small mammals, and birds. Thimbleberries sustain grouse, grosbeaks, jays, robins, thrushes, towhees, waxwings, and sparrows. Thimbleberries are also popular with bears, marmots, squirrels, chipmunks and other rodents. Wolves (Canis lupus), coyotes (Canis latrans) and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) consume blueberries, huckleberries, and saskatoons to supplement their meat-based diet.

However, berries can offer more than calories. In late fall, bears seek out bearberry. Eating its berries and leaves creates a unique blockage in their digestive system that prevents the bears from defecating during their extended sleep during the winter. Don’t try this at home!

The fleshy cones of junipers also serve as the primary source of food in the winter for the Townsend’s solitaire (Myadestes townsendi). These gray birds defend their winter territories in the mountain valleys by belting out a beautiful song (now if only humans would do that). Interestingly, the essential ingredient in gin is the addition of these erroneously named juniper “berries”. Gin originated in the Netherlands in the Middle Ages and the name gin came from the Dutch word for juniper, which is ‘genever.’ However, before you grab a handful of these light purple berry-like cones from female junipers (that’s right, there are female and male junipers) in hopes of getting a gin buzz as you walk the GDT, you should know that the “berries” can be toxic to humans if ingested.

Shrub Security

Beavers use the stems of willows and alders to build their lodges and dams. Willow, alder and red osier dogwood thickets provide thermal and hiding cover for big game and other wildlife, as well as nesting habitat for many small birds.

Dense water birch thickets provide excellent thermal and hiding cover for various wildlife species. As it often overhangs streams, water birch provides important shade benefiting native fish that have evolved in cold water. Linear water birch stands provide protective travel corridors for wildlife. Water birch stands are considered fair cover for elk and good cover for white-tailed deer, mule deer, small mammals, and birds. Water birch provides important habitat for chickadees, vireos, and other songbirds.

Thick patches of Western snowberry and chokecherry provide cover for small mammals and nesting sites for birds. Common and Rocky Mountain juniper also provide secure hiding places for wildlife. Even highbush cranberry provides cover for small mammals and birds.

Shrub Services

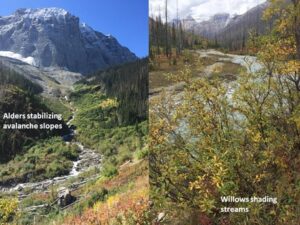

Besides benefiting wildlife by providing food and cover, shrubs provide a wide variety of ecosystem services that foster life support systems like the water cycle, carbon cycle, etc. Willows provide shade to streams, keeping the water temperatures suitable for a large number of aquatic species. The shade benefits terrestrial riparian plants and animals, too. Willows slow water flow and allow the ground to absorb water and nutrients. They stabilize stream banks. They provide construction material for beavers and their dams, which in turn sustain the water table and benefit other ecosystem processes.

Likewise, Sitka alder stabilizes slopes and stream banks and controls erosion on disturbed, nutrient poor sites. As a result, this easy to establish, deciduous shrub has proven useful in land rehabilitation efforts where it has been successfully planted for acid, coal, placer, and copper mine spoil reclamation and soil enrichment. The species can also be used strategically as a conservation buffer by planting it in hedgerows or the shrub row of field windbreaks.

As host to symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria in its roots, Sitka alder is particularly important for improving forest site productivity and has been used as a companion or nurse shrub in some conifer plantations. A US Forest Service study showed that alder added 55 lbs of nitrogen per acre per year to the soil. Canada buffaloberry also has nitrogen-fixing bacteria in their root nodules that allow them to grow in marginal soils. Studies show that this shrub may also concentrate mercury from soil. Wolf willow, not a willow at all but a relative of Canada buffalo-berry, has a similar partnership with nitrogen-fixing bacteria in its root nodules and therefore enriches the soil.

Although they can spread vegetatively by sending up suckers, wolf willows do not form a closed canopy and thus compete little with surrounding vegetation. Other shrubs like the junipers, bearberry, Western snowberry, and white-flowered rhododendron actually repel competitors by exuding chemicals into the soil that discourage the growth of other plants. This keeps plants spaced apart so that moisture and soil nutrient resources do not get used up too quickly.

Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge Values Shrubs

The Indigenous peoples whose traditional territories include the current route of the GDT[9] recognized and valued the different types of shrubs of the Rocky Mountains. Indigenous belief systems accord respect for all aspects of Nature, including shrubs. They see other lifeforms as their kin and their role as one of caretaking, sustaining, and not taking for granted species that provide sustenance for human beings. Traditional harvesting of botanical resources along with ritual and ceremonial practices reflect these respectful interconnected human-plant relationships. With greater legal recognition of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, many First Nations communities in the vicinity of the GDT are restoring their traditional cultural practices and languages, renewing their ties to the land and water, and relearning and applying their extensive ethno-ecological knowledge and wisdom, including how they utilized various shrubs[10].

Indigenous people used parts of willows, including the species found near the Great Divide, for medicinal purposes, basket weaving, to make bows and arrows, and for building animal traps. They also had many practical uses for alders. They derived a red or brown dye from the bark that they used to color wool and tanned animal skins. They used Sitka alder, which is known for being sticky and sweet smelling, as a perfume. They burned alder as firewood and preferred it for smoking fish. They used the hard wood to make snowshoes, bows, and spoons. Traditional medicinal uses included using the inner bark or ointments made from it to treat skin problems such as wounds, skin ulcers, and swellings. They also applied fresh scraped bark juice to the skin to relieve itching from rashes. They used alder to treat digestive issues (both constipation and diarrhea). Leaf decoctions helped treat burns and swollen wounds. Alder roots contain a lot of tannins, so they were boiled and drunk as an astringent. Cold remedies included drinking a decoction of stems, chewing dried stems, and placing dried stems in the nose. They ate the bitter alder catkins and young buds raw or cooked. Although the inner bark was edible, they dried and aged alder bark before consuming it to avoid adverse reactions (i.e., vomiting).

Many First Nations sustainably managed their land by periodically burning areas to foster the growth of berry plants. They often picked berries by breaking off branches and beating the stems with a stick to knock off the fruit. This “speming” method also pruned the shrubs, thus encouraging new growth and more berries in subsequent years. Berries remain an important staple traditional food for Indigenous people. They harvest more than 20 species of berry bushes, including thimbleberries, blueberries, soapberries, huckleberries, and cranberries. The key species for the Ktunaxa, Secwepemc, and Blackfoot nations continues to be the saskatoon.

Canada buffaloberries were also traditionally harvested by several First Nations by using a stick to beat the bush over a piece of canvas or a hide. Dried berries were mixed with dried buffalo meat to make pemmican or added to stews and puddings. These bitter berries were also used medicinally to treat flu, indigestion, and constipation. A juice made from the berries was considered an effective treatment for acne, boils, and gallstones. The berries were also crushed and boiled for use as liquid soap and shampoo. A decoction of the bark was used to relieve eye soreness. The berries were highly valued and traded for with many tribes in areas that lacked Canada buffaloberries.

Indigenous people still cook fresh Canada buffaloberries to make syrup, sauce, or jelly. Nowadays, they may be whisked into a foamy froth and then combined with copious amounts of sugar to make a highly sought-after treat that is still popular today. Traditionally, the berries were whisked with the inner bark of Rocky Mountain maple or with thimbleberry leaves, and thimbleberries were added as a sweetener.

Rich in vitamin C and iron, the bitter berries of the Canada buffaloberry taste somewhat sweeter after several freezes or when dried. The bitter taste of the berries is due to the prevalence of saponins, foam-producing compounds, which can irritate the stomach causing diarrhea and cramps if eaten in large quantities.

Most Indigenous peoples ate chokecherry fruit. They collected the cherries in the fall and dried them, often with the stones left in. They made handles from chokecherry wood. They shredded the bark and used it for decorating basket rims. They made a tonic from the bark for regaining strength after childbirth. Many still use chokecherries for making wine, juice, syrup, and jelly.

Wolf willow fruit is mealy and dry, but some First Nations still utilized them. The Blackfoot peeled and ate the berries or mixed them with grease and stored them in a cool place. This was eaten as a confection or added to soups and broths. The berries were sometimes mixed with blood or sugar and cooked for food. A strong solution made from the bark was used to treat children suffering from frostbite.

The bark of wolf willow was used to make strong fibre baskets useful for collecting berries. Bark was also used to make cords or ropes. Native people discovered that wolf willow had a bad smell when burned. Those who used it for firewood were chided for being lazy. Nevertheless, an essential oil made from wolf willow is currently in demand for aromatherapy.

Wolf willow berries were used by Blackfoot Natives to make seed necklaces. They boiled the berries to remove the fleshy part revealing pointy dark brown seeds with yellow stripes. The seeds were strung onto necklaces or used to decorate the fringes on clothing. When the first European settlers arrived, the new arrivals learned the art from the Indigenous women. Wolf willow seed necklaces became a popular gift to send home.

For indigenous people, harvesting wild shrubs and other plants involves much more than simply taking. A complex protocol, established over thousands of years, governs the process. Two key tenants guide the practice: respect for nature, and respect and caring for each other. Traditionally, many First Nations sang special songs as they got ready for harvests. Often they made an offering of kinnikinnick or scattered some of the first harvest nearby. Another custom involved sharing the first harvest with others in the community.

Shrub Aesthetics

If we take the time to look and appreciate, flowering shrubs like the mountain heathers, prickly rose, shrubby cinquefoil, white-flowered rhododendron, bracted honeysuckle, and saskatoon, as well as species with interesting foliage like the rock willow, wolf willow, red-osier dogwood, Rocky Mountain maple and Rocky Mountain juniper, inspire us with their beauty and enhance our enjoyment of the GDT. As summer wanes and autumn begins, the leaves on the deciduous shrubs along the GDT beguile our eyes with their intense scarlet, orange and gold hues.

In 1841, Sir George Simpson, Governor in Chief of the Hudson Bay Company, crossed the Great Divide in the course of his journey around the world. On reaching the Pass that now bears his name, the adventurous Scot was surprised and delighted to discover mountain heather and wrote about their beauty in his book, Narration of a Journey Around the World. Sometimes, when we are hard at work clearing trail, or on a mission to hike through an area as quickly as possible, we lose sight of that simple pleasure of appreciating the beauty around us. More often than not, we might notice an amazing gnarly old tree or a patch of colourful wildflowers. I encourage you to also see the shrubs along the GDT, and take the time to appreciate their value to wildlife, ecosystems, and Indigenous peoples, as well as their aesthetic contributions.

Is it an Alder or a Willow?

So, back to the start of this article, although the shrubs you see along the GDT are not ALL alders and willows, there are indeed a lot of alders and willows that need to be cut when maintaining the GDT and other trails. Before that work gets done, hikers and equestrians may experience some frustrating bushwhacking experiences, and GDTA volunteers may find the shrub clearing in certain areas very challenging. In both situations, the odd cuss word might turn the air blue. But wouldn’t it still be interesting to know if the source of annoyance is a thicket of alders or willows? Read on, for quick field clues to tell them apart.

Alder shrubs belong to the Birch Family of plants and their leaves look birch-like, i.e., they are alternate, deciduous, smooth, finely-toothed, oval with pointed tips, 4-10 cm long, with distinct veins. Unlike birch tree species, the leaves of alders retain their chlorophyll as long as possible. They thus remain green until they drop from the tree, at which time they turn brown and decompose. The alder has to remake new chlorophyll for its leaves each spring. Alder stems are less flexible than most willow stems and are covered with white dots. Alders bear distinctive male and female catkins on the same bush. The female catkins are on stalks and look like cones. There are several in a cluster. They start off green, and as they mature, turn into brown, woody fruits called strobiles, which bear seeds. The strobiles stay on the bush after the seeds have been released and throughout the winter, making for easy identification.

Willows shrubs belong to the Willow Family of plants. Their leaf shape varies, but none of the willow species found near the Great Divide have birch-like leaves. Willow leaves are alternate, simple, usually long and narrow, and pointed at both ends. Willows reabsorb their chlorophyll and store it in their roots, leaving the remaining yellow, orange and/or red leaf pigments in their leaves, creating lovely fall foliage. Willow stems are smooth, greenish, long, thin and very flexible, especially in new growth. Willows produce catkins that are soft, silky, and silvery before leaves appear in the spring. Catkins remain on the bush after the leaves emerge. As the flowers develop and the anthers form, they appear yellow or pink. Willow species vary greatly in appearance. Some species hybridize, making identification to the species level challenging.

Answers to Skill-Testing Questions for Shrub Connoisseurs

Nature Quiz #1: Blind Test – If your eyes were closed you could tell which species is which by your sense of smell. If you gently crush the leaves or flowers, the one that has a citrus scent is the white-flowered rhododendron and the skunky-smelly one is the false azalea.

Nature Quiz #2: Forb or Shrub? – While the leaves look similar, Devil’s Club is a shrub and has sharp spines. It needs to be carefully pruned well away from the trail. Cow Parsnip is a forb (herbaceous flowering plant) that dies back each year. It has no spines and just needs to be cleared from the tread and immediate corridor.

Nature Quiz #3: Cones or Fruit? – The juniper, being a conifer, has its seeds inside fleshy cones (misnamed juniper “berries”), while alder, being a deciduous shrub, bears fruit called strobiles (misnamed an alder “cone”). Are you confused yet? Nature fascinates and confounds us all.

Table 1. List of the most common shrubs found along the GDT.

| Common Name | Scientific Name |

| Alpine willow/Rocky Mountain willow | Salix petrophila |

| Barratt’s willow | Salix barrattiana |

| Bearberry/Kinnikinnick | Arctostaphylos uva-ursi |

| Black crowberry | Empetrum nigrum |

| Black elderberry | Sambucus cerulea |

| Black gooseberry | Ribes lacustre |

| Black huckleberry | Vaccinium membranaceum |

| Blueberry (oval-leafed) | Vaccinium ovalifolium |

| Bog birch | Betula glandulosa |

| Boulder raspberry | Rubus sp. |

| Bracted honeysuckle | Lonicera sp. |

| Canada buffaloberry/Soopolallie | Shepherdia canadensis |

| Chokecherry | Prunus virginiana |

| Common juniper | Juniperus communis |

| Creeping juniper | Juniperus horizontalis |

| Creeping Oregon-grape | Mahonia aquifolium |

| Devil’s club | Oplopanax horridus |

| Dwarf birch | Betula nana |

| Dwarf red raspberry | Rubus pubescens |

| False azalea | Menziesia ferruginea |

| Grouseberry | Vaccinium scoparium |

| Highbush cranberry | Viburnum trilobum |

| Pink mountain heather | Phyllodoce empetriformis |

| Prickly rose/Wild rose | Rosa acicularis |

| Red osier dogwood | Cornus stolonifera/ Cornus sericea |

| Red raspberry | Rubus idaeus |

| Rock willow | Salix vestita |

| Rocky Mountain juniper | Juniperus scopulorum |

| Rocky Mountain maple/Douglas maple | Acer glabrum |

| Saskatoon/Serviceberry | Amelanchier alnifolia |

| Shrubby cinquefoil | Dasiphora fruticosa |

| Sitka/Green/Slide/Mountain alder | Alnus alnobetula/Alnus crispa/Alnus viridis |

| Sitka mountain ash | Sorbus sitchensis |

| Smooth willow | Salix glauca |

| Speckled alder/Gray alder | Alnus incana |

| Thimbleberry | Rubus parviflorus |

| Water birch/Rocky Mountain birch | Betula occidentalis |

| Wax currant | Ribes cereum |

| Western snowberry | Symphoricarpos occidentalis |

| White-flowered rhododendron | Rhododendron albiflorum |

| White mountain heather | Cassiope mertensiana |

| Wolf willow | Elaeagnus commutata |

| Yellow mountain heather | Phyllodoce glanduliflora |

[1] E-Flora BC is an online biogeographic atlas of the flora (vascular plants, bryophytes, lichens, and algae), fungi and slime molds of British Columbia. See https://ibis.geog.ubc.ca/biodiversity/eflora/

[2] Project: Plant Identification, Alberta, a pictorial and informational collection of plant species. See https://albertaplantid.ca/, especially the Tree and Shrub Species Section – https://albertaplantid.ca/tree-shrub-species/

[3] One of the world’s most popular nature apps, iNaturalist helps you identify the plants and animals around you. Get connected with a community of over a million scientists and naturalists who can help you learn more about nature! iNaturalist is an easy-to-use database that records worldwide biodiversity. iNaturalist users worldwide upload photos of wild living things to the site that can be used as scientific data. See https://inaturalist.ca/home

[4] A variety of Rocky Mountain maple (Acer glabrum) found on the west side of the Great Divide to the Pacific Coast is called Douglas maple (Acer glabrum, var Douglasii).

[5] Many willow species hybridize, making identification challenging.

[6] Alnus alnobetula is the correct scientific name even though in some texts, this species is called Alnus viridis or Alnus crispa, which are illegitimate botanical names. On the B.C. side of the great divide, it is usually called Sitka or slide alder whereas In Alberta, it is usually called green alder or mountain alder. It can be confusing as Alnus incana usually known as speckled alder is also sometimes called mountain alder.

[7] The term “mountain heather” describes a group of low growing plants from the Heath family of plants (the Ericaceae). Other common names include moss-heather, moss-bush, Cassiope, bell flowers, or heath. Among the most representative shrubs of high mountain habitats, mountain heathers form low trailing sub-shrubs or mats as an adaptation to the harsh environments of the upper elevations. Besides hugging the ground, other qualities that allow these plants to exist under harsh alpine conditions include having glandular hairs on their herbage for warmth; scale-like evergreen leaves for moisture retention, and wind-resistant flowers that are short and stiff or leathery and bell shaped.

[8] A future article will help identify the edible as well as toxic berries along the GDT.

[9] Indigenous People have called the Rocky Mountains home since time immemorial and used the passes along the Great Divide as trading and hunting routes. Today, the GDT passes through the traditional territories of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Tsuut’ina, Ĩyãħé Nakoda, Cree, Lheidli T’enneh, Ktunaxa, Secwepemc, Sinixt, and Métis.

[10] A useful resource is the book Edible and Medicinal Plants of Canada by MacKinnon, Kershaw and Arnason (2016).