Thoughts on Tagging the GDT

By Dave Higgins

Sure, there are more up-to-date options available nowadays if you want to follow precisely a defined walking route, or track, through untamed spaces between two widely-separated terrestrial points on this planet. For example, you can purchase a highly sophisticated electronic gadget that receives coded digital transmissions from several even more sophisticated objects in medium earth orbit 20,200 km above the surface, with the kind (and hopefully uninterrupted) blessing of the U.S. military’s Space Force agency, and simply adhere to the course indicated by the wiggly line highlighted on your little device’s tiny display. Just don’t lose it in the next stream you cross, and remember to appreciate to the fullest your escape from modern civilization and all its trappings.

As for me, I prefer a decidedly low-tech system of physical markers, or what we old-timers call signs and blazes, to show the way (but since I’m an admitted old guy, you could have expected that!). I know – signs and blazes create clutter, are unnatural and compromise the wilderness experience (as alluded to in the previous paragraph). In my defense, though, I prefer a bare minimum of signage and loathe the traditional blaze (a slash made with an axe on a tree trunk), favouring a painted-on facsimile out of concern for the health of the tree as well as the sensibilities of the observer.

With my bias out in the open, then, here we go with my (hopefully) convincing arguments in support of the lowly paint blaze. But first, some background details:

A PATH TO ADVENTURE

When I first set foot on Ontario’s Bruce Trail in 1970, at the tender age of 16, and noticed the small rectangular white marks painted on trees leading off through the forest in both directions, what struck me was the notion that I could follow those marks for days, weeks and perhaps months, and eventually come to the famed Niagara Gorge or, in the opposite direction, the northern tip of the storied Bruce Peninsula, and who knows what treasures and experiences I’d encounter along the way? In a very real sense, those paint marks were an enticement to discovery and adventure.

A few years later, after hiking most of the Bruce Trail and learning the hard way to always be on the lookout for blazes and to not miss a change in direction, I began attending organized work outings and learned the craft of trail maintenance and, of course, paint blazing. The acknowledged pro was a fiftyish Kiwi named Chris Horne, and he taught me to make perfect two-by-six-inch blazes. The idea, Chris said, was to lessen the intrusive aspect of the paint marks by keeping them as uniform and tidy as possible, so that the hiker is less conscious of their presence. Think of official signs along highways – if they all look the same you barely notice them, unless of course, you’re on the lookout for where to turn or need reassurance that you’re still on the right road.

I also learned that the idea of rectangular paint blazes to mark trails was originated in the U.S., by the Appalachian Trail Conference in the 1950s. That footpath crosses many roads, makes innumerable abrupt turns, intersects countless other trails, and traverses long stretches of bare ground and rock. From my personal experience on over 1000 km of the AT, a uniform system of markers is crucial to staying on the main path and avoiding constant backtracking or searching for the correct route. And from the perspective of a thru-hiker doing long days on a tight daylight budget, unnecessary steps and lost time are to be avoided like the plague.

OTHER MARKERS

Paint blazes aren’t the only system of standardized marking used on long distance trails. There’s also what we refer to as a “reassurance marker” – a small metal or plastic placard bearing the trail’s official logo, nailed to trees or posts. For cost and other reasons, these markers are usually placed about an hour’s hike apart. Aside from confirming to trail users that they’re indeed on the correct route, for some (like the author) there’s also a kind of intangible emotional reaction when encountering this kind of marker – that they’re on the actual honest-to-goodness official path, and thus participating in a grand and marvelous endeavour.

Another type of marker occasionally seen (and invariably appreciated by users) is a small sign pointing the way to a campsite, access point, or perhaps a water source off the main trail. Larger, more descriptive signs can also be found, normally only at access points, but to me these are a necessary evil – like the set of rules posted at public swimming pools – an admonishment to the irresponsible to not wreck the trail and the experience for other users. One thing I like to see at these locations, though, is an indication of trail direction, e.g. north or south.

BLAZING ON THE GDT

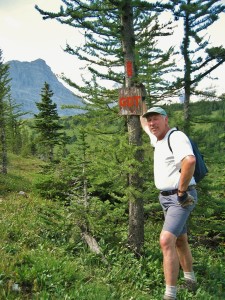

But this is a piece about trail blazing, so I’ll get back on topic and discuss what we’re doing and why on the Great Divide Trail. Years ago, 1976 specifically, we put forward a detailed proposal to the Alberta government to obtain permission to begin construction of the Trail in the upper Highwood River watershed. For consistency with other trail systems, white paint blazing was part of the proposal, and long story short, they were in agreement but requested that we use “Forest Service Orange,” which was what they sprayed on trees to demarcate blocks of forest slated for study or harvest. They even provided us, helpfully, with a pallet-load of this stuff, probably enough to paint every tree top to bottom from Banff to Waterton. An awful colour, we thought, and even worse it was a thin lacquer, suitable only for spraying. So we found, at Canadian Tire of all places, a marine grade oil-based enamel that was a close match to Forest Service Orange, and only used the other stuff as thinner!

Why oil-based paint, you ask, instead of the more user- (and environmentally) friendly water-based latex? First and foremost, for longevity and durability. Realistically, we can’t be re-blazing every couple or even every few years. The correct paint will last decades when applied to the right surface (the smooth bark of subalpine fir is awesome). Other reasons: you can apply oil-based paint in cold or wet weather, and one coat is sufficient. As it turned out, the bright orange colour was an inspired if unintentional choice – we were out on the newly-marked Trail after an early snowstorm, and those orange blazes were easily distinguished from the patches of white snow plastered on tree trunks at higher elevations. And with the path obscured it was still possible to follow it.

Over the course of the late 1970s and early 1980s, we blazed the GDT from Fording Pass south to Tornado Mountain, a trail distance of about 100 km. As of today this is still the only section that’s so marked. With the expanded scope of the GDT in recent years, national and provincial parks are now traversed by the official route, but it’s highly unlikely there will ever be paint blazing in those jurisdictions. Not that there needs to be; unlike non-park sections of the route, there are few road crossings or unmarked trail intersections and no cutlines or logging roads to cause confusion, and all trails used by humans are more or less official and therefore signed and maintained (again, more or less!).

Non-park GDT routes of cultural significance, such as the David Thompson Heritage Trail in BC, probably won’t be blazed either, (although an occasional, well placed reassurance marker may be used) to preserve both the historical integrity of the place and quality of user experience. However the route linking Amiskwi Pass with the David Thompson trailhead, which alternates logging roads with single-track segments, is a good candidate for marking.

I’ve talked to many people who’ve hiked the entire GDT or just portions, and to date the only feedback on the blazed section has been positive. As might be expected, for most the hiking experience becomes more relaxed and enjoyable when it’s not necessary to be continuously route-finding. If there’s a negative, though, it’s that the user can become overly dependent on an uninterrupted series of blazes, which underlines the importance of ongoing inspection and maintenance, as well as good standards.

This is harder than it might seem. If the GDT was always a pathway through the forest, maintaining a uniform, unbroken system of paint blazes would be a breeze in the trees. Instead, long stretches traverse meadows, ridgetops and mountain passes, making it difficult to find and preserve blazing opportunities. Paint on tree trunks in higher-elevation exposed locations, for example, gets blasted away by severe weather within a few years. The most effective solution is an old one: stone cairns, but with the addition of a painted vertical finger of rock at the top (no particular offense intended, but commonly taken by the hapless hiker caught out in appalling weather!). Of course, this pre-supposes a supply of suitable rocks nearby, which, bizarrely, can often be hard to find in the Rocky Mountains. We’ve also tried wooden posts supported by rocks, but wind and snowslides usually make short work of them. So in the long run, it may be necessary to haul metal posts into certain locations where they can be securely anchored.

BLAZING HOW-TO’s

I’ve touched on the importance of good blazing practice, and some reasons why it should be adhered to. I’ve also mentioned that it can be tough to do that. But there are three things it’s easy to stick with in forested sections, and those are size, placement and spacing. I always instruct volunteers to paint nice neat, square-cornered blazes as close to 50mm wide by 150mm high (or 2” x 6”) as possible, so that they don’t stand out from each other. Slightly larger blazes are permitted if it makes them easier to find, for example at the far side of a clearing.

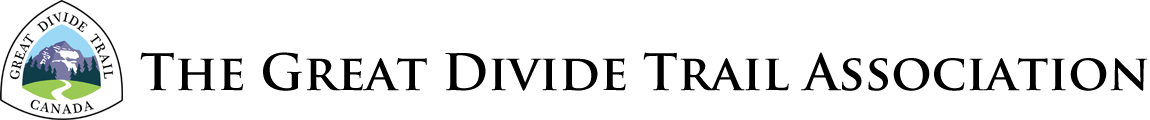

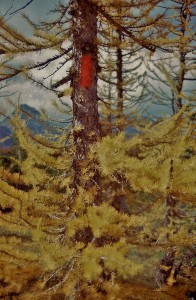

How NOT to Blaze – The author blazing too low on the wrong kind of tree, circa 1978 (before he became a pro)

Blazes should always be located just above eye level for an average height person, and if at all possible on a mature (but not TOO mature) tree that’s likely to remain alive and standing for the next few decades. The tree chosen should be visible from a point 25 to 50 metres back down the trail, and the blaze should be centred on the tree: blazes are always positioned to be seen in the direction of travel. Over the years we’ve managed to stay close to this ideal, but we’ve often painted too many blazes where the trail is perfectly obvious, creating visual pollution. Nowadays I advocate the bare minimum we can get away with – no less than 100m apart and preferably twice that distance, so that you see a blaze no more frequently than, say, once per minute unless the way ahead is hard to discern. I like this quote from Canadian climbing legend Brian Greenwood: “Blazes should make the route intelligible, but only enough so that the adventure is preserved.”

A double blaze (one above the other), indicates the Trail abruptly changes direction at that point – again, unless the way forward is obvious. In some cases the upper blaze is offset from the lower one to show which direction the trail turns. Another single blaze is usually visible from the double, confirming the new direction, for example where a footpath tee’s into a cutline.

WHAT ABOUT SPRAY PAINT?

Often, while demonstrating paint blazing techniques, new volunteers ask why I use a brush and not a spray can with a template, which would be faster and produce a more uniform result. I’m tempted to reply that I’m NOT into tagging! The next best answer is cost, but spray cans also produce a lot of waste and aren’t practical to carry in quantity for long distances. Other good reasons: handling a wet template would be a lot messier than a brush, and spray paint is so thin it requires a second or third coat, making it more likely to run down the tree trunk (the worst sin a paint blazer can commit!).

Spray paint does have a role to play, however. When we reroute a section of trail, it becomes necessary to get rid of the blazes on the old route. The most efficient and least harmful way to do this is NOT to cut them off with an axe (as I’ve seen done by vandals), it’s to paint them over with a grey-brown flat primer spray.

ACCESS TRAILS

Trails that provide access to the GDT, or access from the GDT to points of interest such as campsites, may also be marked but with blue blazes. The same system applies: one blaze – the trail continues; two blazes – the trail changes direction. Only a few such trails have been deemed worthy of blazing; usually where there’s a good chance of losing the route in a maze of old logging roads and cutlines.

Junction of GDT and Baril Creek access trail showing blue blaze. Photo courtesy of Erin (“Wired”) Saver

THAT’S ALL, FOLKS

So there you have it – paint blazing is a time-proven system of denoting the route of a trail and helping users avoid getting lost. But it can never be a perfect system; time, nature and sometimes humans themselves take their toll on anything we add to the landscape. The fact the Trail is blazed doesn’t change the need for map (and/or GPS), good route-finding skills and plain old common sense. And that suits an old-timer like me just fine.